| |

|

Park Güel, one of the mayor works of Catalan architect Gaudi in Barcelona. |

| |

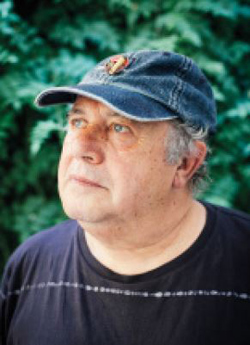

Josep (Katy) Baltierrez i Alier

Secretary of ARSEC

Representative for the Cannabis Social Club Candidacy |

|

Josep Baltierrez I Alier, el Katy, was born in 1946 in Manresa, a small industrial town some sixty kilometers north of Barcelona in the heartland of Catalunya. Groomed to join the management of the family’s textile plants, Josep had other plans. In 1964, with his high school diploma in his pocket, he left the comfort of the family home to join the ranks of the resistance to the regime of the “putschist” Franco in Madrid

While studying Political Science and Sociology at Madrid’s Complutense University, Josep participated in 1967 of the foundation of the clandestine Democratic Student Union of Madrid, becoming its first secretary. Being from Catalunya, his fellow students called him El Catalan, a nickname that over time morphed into Katy, the name that stuck to him ever since.

Soon afterwards he joined the politically more active Popular Liberation Front (Frente de Liberación Popular). After the Front’s dissolution in 1969 Baltierrez and likeminded unconditional anti-Francoists, formed in 1971 the Revolutionary Communist League (Liga Comunista Revolucionaria), a Trotskyist organization, member of the Fourth International. To understand this epoch in Katy’s life we get some help from Francisco Fernandez-Buey, who wrote a “Personal Memory of the Foundation of the Democratic Student Union of Barcelona”. He had participated of that March 9, 1966 clandestine foundation and reminds us at a distance of almost fifty years of the repressive climate of those days.

|

|

|

|

“A few weeks before March 9, the SDEUB (the Union to be

founded) board of delegates had obtained the permission of the Capuchin Fathers to hold the constituent assembly in the Convent of Sarriá. One day before March 9, only about twenty people knew the place. To evade surveillance, we followed a rigorous procedure: each one of the delegates from the faculties and university schools summoned, one by one, the rest of the representatives of each academic center in different central places of the city at a pre-set time. From these points of rendezvous, separated in small groups and following different itineraries, the Convent was reached with the maximum speed. In other places the intellectuals and artists invited were picked up, gathering most of them in a house near the Convent. …/…

Through an unforeseen mistake, the feared political-social brigade found out about the meeting. But by then, the SDEUB had already been constituted. Before the police surrounded the building the Declaration of Principles, the Manifesto for a democratic university and the Statutes had already been approved, by acclamation and with the condition that they were later ratified by the assemblies of each one of the university centers.” |

|

By surrounding the convent, the police caused un uproar that initiated a spontaneous general strike in Barcelona, with demonstrations of solidarity extending to Madrid, Valencia, Sevilla and other parts of the country. Eventually the students had to leave the convent and surrender(!) to the police, but due to the national uproar and attention, all of them were released shortly afterwards. The humorous note to this whole episode was provided by the dictatorial government itself, when it claimed that the proceedings had been undemocratic, because the Union had been approved by general acclaim of all those present and should instead have been voted on and the votes counted!

Fernandez-Buey makes another interesting point in his ‘memorial’. He draws our attention to the fact that the principal protagonists of the foundation of the student union were the communist students. These students were not only well organized and willing to take risks, but “they were the best students in each Faculty …/… with exemplary democratic behaviour, that is, respectful of what was decided in the assemblies. [That explains why], despite the fierce anti-Communist propaganda of the regime, the majority of the students … of that epoch, “identified communism with the struggle for democracy”.

It is hard to imagine nowadays – when students address their professors by their first name – how different it was in Franco’s Spain. Academic life had been militarized, and professors were appointed for loyalty to the regime, their competence for their position being of secondary importance. Following the rules of the barracks of any army, critique of a professor’s opinions, or talking back to him, was not accepted. No wonder the students felt ridiculed and humiliated, wondering how they could change the nightmare awaiting them each morning. No wonder lots of them joined the communist party ranks, apparently the only political organization run with respect for the voice of the ‘demos’.

|

|

|

The Guardia Civil surrounded the

convent |

When in 1969 Katy ’s father died prematurely, his family wanted him to come back to Manresa to help manage the family business. But his heart told him to pursue the struggle against the regime, causing a painful estrangement from the people dearest to him. To make matters worse, it is about this time that the academic authorities became aware of his clandestine involvement, causing him to be expelled from the university. Katy accepted the situation as part of the struggle for democracy and remembers with fondness his ‘humanist’ economics professor Jose Luis Sanpedro and his anarchist philosophy professor Augustin Garcia Calvo, separated from his chair for supporting the protesting students.

From this moment on and until the dictator’s death in 1975, Josep lived in a regime of complete clandestinity, dedicating himself entirely to the fight against the regime and the capitalist system that sustained it.

The year 1975 was an extraordinary one for Josep, when his first daughter Laia was born, fruit of his romantic relation with his comrade and companion Rosa Meras.

Then, on November 20th, the hated dictator died. The next evening, a bottle of champagne, gift of his late father to celebrate the occasion, heightened Josep’s spirits in the company of his friends, who insisted he try some hashish.

| |

|

“It was on November 21, 1975, the putschist dictator Francisco Franco had died the previous day. The reason why at 29 years of age I had not had the opportunity to experiment with cannabis and other psychoactive substances - apart from alcohol - was due to my clandestine political militancy. On the one hand there were security reasons: mixing the world of drugs and the clandestine world was dangerous and the party forbade it. On the other hand, communist morality prevailed, in which the only admissible drug was revolution.”

“The mixture of cava and hashish produced a state of euphoria and gave me feelings of peace and hope for the future that was opening up in Spain. I remember that with my comrades we went out into the street and, breaking all the rules of security, we proclaimed and celebrated the death of the fascist in a reckless attitude among people who were mourning the dictator’s departure. We had to escape running from their ire.

When I returned home I told a long story to my daughter Laia, who was 4 months old at the time and then I fell asleep peacefully. The next days the effects of the hashisch did not stop accompanying me and helped me to relativize the communist moral and to undertake new flights.” |

With the end of the dictatorship the revolutionary movement in Spain was doomed to extinction. Katy proposed the dissolution of the party in favor of other political movements that sprouted in the new society. When his proposal was defeated he abandoned the League and decided to return to Catalunya, settling in La Floresta, Spain’s last hippy reserve, “where the smoke of joints seemed to mix with the early morning mists”.

But that smoke didn’t come from Kathy’s joints, since he would make the morning commute to the old gothic centre of Barcelona where he was now managing the bookstore Leviathan, two steps from bookstore Makoki. Here he got to know the world of the comics, the graphic revolutionaries protesting the ‘patrolled democracy’, and became an assiduous participant of the lunches in “El Mercadillo’. During prolonged desserts, “well-moistened and better smoked, amid speculations and discussions, surged the idea of creating the Cannabis Consumers Association of Catalonia (ACDCDC), the original name which was replaced by that of ARSEC, in homage to Ramón Santos, friend and great defender of cannabis users accused of crimes against the public health. Recently the socialist government of Felipe Gonzalez had, under pression from the Big American Brother, made the public possession and consumption of cannabis a punishable infringement of the law. “From the rage for the harassment that was coming upon us ARSEC was born.”

Katy wrote the manifest, Jaume Torrent, the lawyer put the seny, an ancestral Catalan term for knowledge, and Felipe Borrallo led the operation. As mentioned on other pages of this site, with the arrival of the ‘farmers’ from Vic, led by their ‘captain’ Jaime Prats, the collective growing of marihuana made its entry in the imagination of capitalist society. This was the revolutionary anti-capitalist action Katy had been waiting for since the days he had left home to fight the dragon in Madrid. It didn’t matter that the dragon now lived in Washington and went by the name of Uncle Sam. Growing cannabis and consuming it without the intervention of any capitalist middleman was a communist dream come true, a slap in the face of the prohibiting monster.

Katy’s long career in political organization now came in handy. According to him, cannabis users had to unite, in Spain, and beyond its borders. They could learn about its history and its cultivation, help each other organize and defend against the agents of prohibition. And then of course there was the possibility of interchanging weed. In his travels across the European continent, Katy learned a lot about local situations and in turn explained to his foreign interlocutors the Spanish experience. And to top it off he would produce a joint of homegrown weed, one that back at Makoki, had been baptized 'Ha-Ha', and got everybody to laugh,

Yes, that's what marihuana has done for the Old Continent, where the laughing had stopped since the Inquistion exterminated the voice of nature. Now, at the hand of Maria, people became happy again, happy for existing, overcoming spleen, discontent, nihilism and all those existential problems that have afflicted the alienated populations of modern times.

The nineties were very happy years for Katy, in his family life with the birth of Cadi and María, fruit of his relationship with his companion Antonia Giménez, and on the social level for the growing acceptance of marijuana by the population and its political representatives. In 2001, for the tenth anniversary of ARSEC, Katy wrote in a kind of continuation of the founding manifesto:

|

"That joint that crossed the world dragging the chains of prohibition, of police persecution, of marginalization and fines, of jail and clandestinity ....it seems that lately it has found refuge in hospitals, among people with cancer, multiple sclerosis, glaucoma or other diseases, so that cannabis, thanks to its palliative or curative properties, is today an indisputable therapeutic reference." |

|

In these same years, parallel with his cannabis activism, Katy had an outstanding participation in the campaign against the genocide of the Bosnian people during the Balkan War. Together with María Permanyer and José Mª Mendiluce, he was one of the founders of EUROPE FOR BOSNIA, a platform of various associations that organized a movement of political denunciation of genocide towards the public authorities, as well as a campaign of material solidarity with the people of Sarajevo.

On a professional level Katy was involved in research on youth unemployment and social exclusion in the Faculty of Sociology of the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Currently Katy believes that, the apparent tolerance of cannabis in Catalonia, as represented by the acceptance of consumer clubs, hides the harsh reality of fines, crop confiscations and mafias of all kinds without any regard for the beneficial effects of the plant, just interested in easy money. Since people can acquire marijuana they no longer think about changing the laws.

"If the free supply was opened to people with diseases susceptible to being treated with maria - free supply as a symbol of our cause - others were the courses in which our dreams were diluted. The hyper marketing of marijuana cultivation and its expensive consumption in private 'tolerated' clubs meant the passage from struggle to submission."¹

Although disappointed by the preponderance of the commercial aspect of the cultivation and supply of the plant, Katy does not lose hope that slowly things will change and the right of each one to cultivate and consume will prevail. "Let's see if one day we can give it again as a present ... and smoke it legally and without worrying, with our children."

With this dream in mind Katy has accepted with enthusiasm to represent the candidacy for the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the Cannabis Social Clubs. "I consider the nomination as an honor for my person and a vehicle for the joint to find refuge among the general public, aware that this plant that has been vilified for millennia is a gift of nature, a remedy for the happiness of the individual person and the wellbeing of the whole community. Let the campaign begin!"

We are happy and honoured to present Josep (Katy) Baltierrez i Alier as one of our candidates for the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize in representation of the Cannabis Social Clubs. His pioneering work to help lead the 'movida cannabica' and help create the 'Catalan Breach' in the Spanish prohibitionist enclosure, has enabled all of us a model for the responsible and sociable use of cannabis.

¹ Cáñamo magazine Nº 243, page 64, July 2016, "25 years ARSEC"

|

|